What You'll Learn

- • The three types of FAI and how they affect athletes

- • Why FAI is common in certain sports

- • How to assess and identify FAI in your athletes

- • Practical training modifications that actually work

- • Sport-specific considerations for baseball and soccer

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) is one of those issues that's become a hot topic in both sports medicine and the performance world. At its core, FAI happens when there's abnormal contact between the ball (femoral head) and the socket (acetabulum) of the hip joint. Over time, that extra friction can cause cartilage damage, labral tears, and eventually even early-onset osteoarthritis. If you're working with athletes or active individuals, it's something you can't really ignore.

What Is FAI?

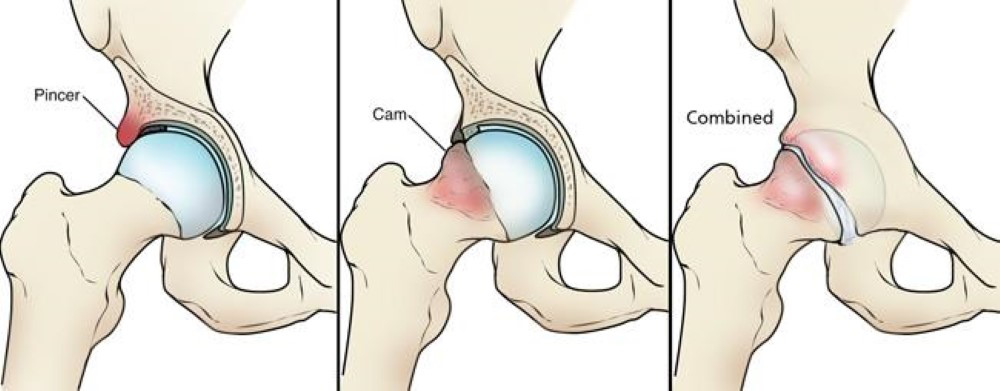

At its core, FAI happens when there's abnormal contact between the ball (femoral head) and the socket (acetabulum) of the hip joint. Over time, that extra friction can cause cartilage damage, labral tears, and eventually even early-onset osteoarthritis.

The Three Morphologies

Cam

Extra bone at the femoral head–neck junction creates an aspherical "bump." Flexion/internal rotation is the classic aggravator.

Pincer

Excess acetabular coverage (often from retroversion or deep socket) compresses the labrum—flexion and adduction can be provocative.

Mixed

Features of both—this is the most common presentation in competitive athletes.

Where Does FAI Come From?

FAI is multifactorial: part biology (how your hip is built), part exposure (how you've used it), and part behavior (how you move). Two big buckets:

Developmental/Biological

- • Hip shape varies across individuals and populations

- • Femoral head size, acetabular depth/coverage differences

- • Some differences are heritable and cluster by ancestry

- • Sex differences: males more often cam, females more often pincer

Environmental/Loading

- • High-volume, high-intensity sport during skeletal maturation

- • Year-round hockey, soccer, baseball linked to cam formation

- • Earlier contact between femur and acetabulum

- • Repetitive loading patterns during growth

Descent, Sex, and Morphology—Why This Matters for Coaches

Population studies show that baseline hip shape isn't one-size-fits-all, and that has coaching implications:

Population Differences in Hip Morphology

- Ethnicity: In professional male soccer players, large cam deformities were common overall, but markedly lower in East Asian athletes; acetabular dysplasia was least prevalent in White players.

- Race/Sex differences: Population imaging shows Chinese cohorts with shallower, narrower sockets and reduced femoral head coverage relative to Caucasian and African American cohorts.

- Ancestry-based hip structure: According to Stuart McGill, Eastern European populations often have deeper hip sockets, allowing for greater squat depth, while Celtic/Scottish hips tend to be shallower.

💡 Coaching Takeaway

Don't stereotype anyone's hips. Build the program around the athlete in front of you and respect individual morphology. Two players can tolerate very different hip depths and squat depths before symptoms appear.

How FAI Shows Up in Sport (and Why Pelvis Position Isn't the Whole Story)

Sports with frequent deep hip flexion + rotation (hockey stride, soccer strike/plant, baseball swing/slide step) ask a lot from the anterior hip. Athletes often operate in a more anteriorly tilted pelvis during play, which narrows the margin for error in flexion/internal rotation.

Briefly: a touch of posterior tilt can delay bony contact and buy room for flexion/internal rotation—but it won't change bone shape. Use it as a symptom-management lever, not a cure.

FAI and Sports Performance: The Real-World Impact

FAI doesn't just show up in the weight room—it can directly influence performance on the field. Any activity that requires deep hip flexion, rotation, or rapid directional changes can be affected by hip morphology. Let's break down how this plays out in specific sports.

Baseball

Pitching

Proper hip rotation is essential for generating force from the lower body. Athletes with cam or pincer morphology may experience reduced internal rotation or end-range flexion, limiting the ability to fully load the hips and transfer energy through the kinetic chain.

Hitting

The hip rotation needed for a full, powerful swing relies on smooth internal and external rotation. FAI can cause early contact between the femoral head and acetabulum during the swing, forcing the hitter to adjust stance or reduce rotational velocity.

Soccer

Striking Mechanics

When striking a ball, the hip undergoes flexion, adduction, and rotation simultaneously. FAI can restrict this range, causing players to adjust their approach or use compensatory movements through the pelvis or lower back.

Plant Mechanics

Planting the support leg for a shot or sprint demands hip stability and rotation. Limited hip internal rotation can shift stress to the knees and spine, altering mechanics.

Porter Hodge demonstrates the complex hip mechanics required during pitching delivery. The landing leg (stride leg) undergoes significant hip flexion, internal rotation, and deceleration forces that can be compromised by FAI morphology. Hip impingement on the landing leg can limit stride length, reduce energy transfer through the kinetic chain, and force compensatory movements that may increase injury risk.

Image source: MLB Photos

Soccer players demonstrating the complex hip rotation demands during play. The striking player (center) shows the hip external rotation and flexion required for ball contact, while the defending players demonstrate the rapid internal and external rotation needed for directional changes and defensive positioning. These movements place significant demands on hip mobility and can be limited by FAI morphology.

Image source: Sports Injury Bulletin

Monitor how athletes move in sport-specific positions—don't just rely on gym assessments. Encourage mechanics that respect each athlete's hip morphology and range-of-motion limits. Consider rotational drills, mobility work, and strength programming that target hip and core control to maximize performance while minimizing discomfort.

Weight Room "Tells" You'll See with FAI

These are performance indicators to watch for:

- Persistent toe‑out/external rotation to find clearance at the bottom of a squat

- Shallow depth or early hip pinch in front‑loaded squats, high‑bar squats, or deep hinges

- Compensatory shift toward the less irritable side coming out of the hole

- Front‑side restrictions in split work (front foot elevated split squats feel fine, rear‑foot elevated provoke)

- Limited seated/90–90 internal rotation compared to external rotation, especially when hips are flexed

Programming & Corrective Strategies

Assess and Individualize

- • Screen active hip flexion, IR/ER at 90°, squat pattern, and symptom behavior

- • Compare sides for asymmetries

- • Note stance width, toe angle, and bar/load position that feel best

Adjust the Pattern

- • Squat family: stance width, box squats, safety-bar squats

- • Hinge family: trap-bar deadlifts, RDLs, hip thrusts

- • Split/step work: front-foot elevated split squats first

Create Space with Position

- Cue a light exhale and rib-to-pelvis connection before deep positions

- Pair deep patterns with abduction/external rotation isometrics

Mobility Where It Counts

- Soft-tissue work to anterior hip/capsule neighbors (TFL/rectus femoris/adductors), then active IR in moderate flexion ranges

- Thoracic rotation and pelvic control drills to distribute motion demands

Load What Doesn't Irritate

Focus on hinges, sleds, jumps, and med-ball work while modifying provocative squats. The key is respecting the 24-hour symptom response and progressing angle and volume more than chasing novelty exercises.

Communicate with the Medical Team

When you encounter persistent mechanical blocks, catching or clicking sensations, or pain that doesn't respond to conservative modifications, it's time to refer out for imaging and consultation with an orthopedic specialist or hip-savvy physical therapist. Early recognition of when to escalate care can save months of frustration and prevent further tissue damage.

Sport-Specific Programming Notes

Hockey

Repeated deep flexion + IR/ER in stride and turns stresses the anterosuperior labrum. Expect pinch in front-loaded squats; lean on hinges, lateral work, and controlled-depth squats. Focus on maintaining hip mobility for skating stride efficiency.

Soccer

Strike and plant mechanics challenge flexion/adduction/IR; sprint drills that bias upright torso and good pelvic control reduce irritability. Favor split stance and hinge variations during flare-ups. Address both kicking and support leg demands in training.

Baseball

Pitchers and hitters live in asymmetrical rotation; manage total hip flexion volume on the lead side, incorporate deep squat holds with thoracic spine rotations to address asymmetries, and feed med-ball/lateral work for power. Monitor stride mechanics and swing patterns for compensations.

Bottom Line

FAI is a shape + load + behavior problem. Your job isn't to "fix bones," it's to coach around them: find the angles that fit, build capacity there, and keep the athlete's skill work rolling. Use pelvic position as a small dial when symptoms flare, but build your plan on smart exercise selection, individualized stances, and great communication with your medical partners.

References & Additional Resources

1. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. (2024). Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) - Hip Anatomy and Impingement Patterns.View Anatomical Diagram

2. McGill, S. (n.d.). Hip Anatomy: Key Concepts for Athletes and Coaches. OTP Books.Retrieved from OTP Books

3. Agricola, R., Heijboer, M., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M., et al. (2014). Cam impingement of the hip—a risk factor for hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 22(5), 714–720.https://www.oarsijournal.com/article/S1063-4584(19)31273-7/fulltext

4. Siebenrock, K. A., Ferner, F., Noble, P. C., et al. (2016). The cam-type deformity of the proximal femur arises in childhood in response to vigorous sporting activity. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 474(4), 895–902.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27492971/

5. Cressey, E. (2014). Hip Pain in Athletes: The Origin of Femoroacetabular Impingement.https://ericcressey.com/hip-pain-in-athletes-the-origin-of-femoroacetabular-impingement/

6. Sports Injury Bulletin. (2024). Femoroacetabular Impingement in Soccer Players.https://www.sportsinjurybulletin.com

7. MLB Photos. (2024). Porter Hodge Pitching Mechanics.https://img.mlbstatic.com/mlb-photos/